This article is written by François Lévy, BA, MArch, MSE, AIA, NCARB, AIAA. See more of his work with François Lévy Architecture + Interiors by clicking the link.

Most people understand that the work of architects and allied professions is the design of buildings. And, of course, it is. Whether working as “traditional” architects, academics, researchers, building scientists, interior designers, landscape architects, architectural technologists, in any number of engineering disciplines, building product representatives, architectural technologists, or specialized fabricators—the broad umbrella of design professionals unquestionably devotes much of its time, energy, and expertise to the built environment. Buildings — whether actual or unbuilt — are essential to architecture. Essential, but not sufficient.

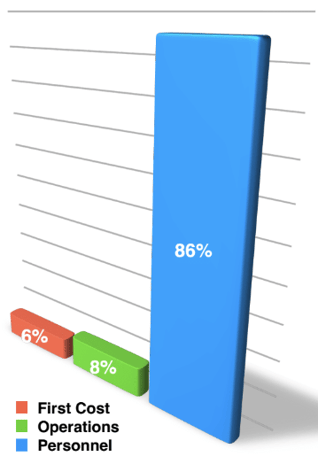

A professor of mine once started a graduate classroom discussion: “What’s the most valuable component of a building?” A lively debate ensued, and eventually we weighed whether a building’s first costs — construction — were outstripped by its operating costs. After some digging, we concluded that for a typical building, operational costs significantly outweighed first costs. Just as we settled on this consensus, our professor added, “And what about the most valuable component of a building — its occupants?” And so in our deliberations we vastly undervalued — economically speaking — a building’s occupants. It turns out that the employment costs alone of a building’s occupants outweigh first and running costs combined by a factor of six or more, according to a US Forest Service study.

A professor of mine once started a graduate classroom discussion: “What’s the most valuable component of a building?” A lively debate ensued, and eventually we weighed whether a building’s first costs — construction — were outstripped by its operating costs. After some digging, we concluded that for a typical building, operational costs significantly outweighed first costs. Just as we settled on this consensus, our professor added, “And what about the most valuable component of a building — its occupants?” And so in our deliberations we vastly undervalued — economically speaking — a building’s occupants. It turns out that the employment costs alone of a building’s occupants outweigh first and running costs combined by a factor of six or more, according to a US Forest Service study.

In our work, naturally we focus much of our initial time and energy on clients and stakeholders, particularly in a project’s programming phases. Soon enough, though, we become fascinated by the product of our design. So much so, that we run the risk of losing sight of the most valuable part of any project: people.

First Principle of Architectural Design

I have two fundamental design principles to suggest that can help us all keep my former professor’s valuable lesson in mind. The first one is this:

Design for People

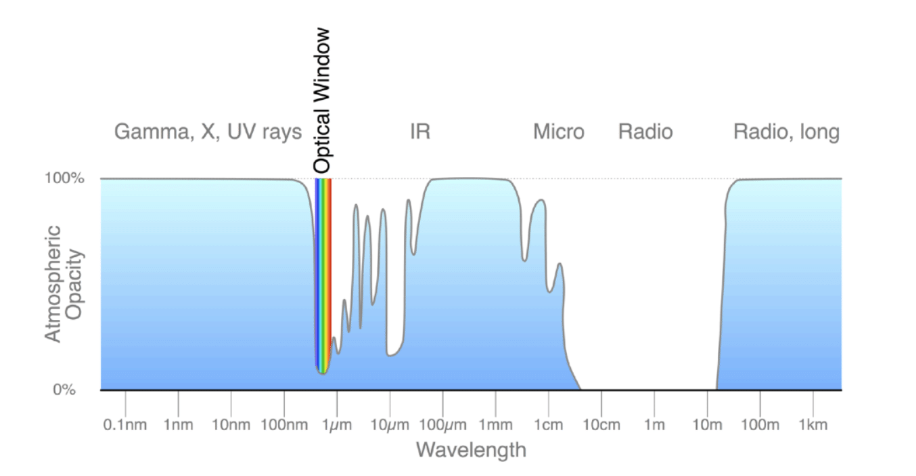

Designers train for years, first in school, then in practice, to understand buildings as complex systems of systems, and then to appropriately apply that knowledge. While the lines we draw and volumes we model and render are all about the materials that buildings are made of, ultimately the function and purpose of a building is to be inhabited by people. And people are the product of adaptive evolution in a particular environment, our planet. One small example: eyes see color the way they do because of a particular tiny window in our atmosphere that allows a very narrow band of electromagnetic energy just below the micrometer wavelength (what we think of as visible light) to easily penetrate to the surface of our world.

Design for People is thus the application of biophilic design as a consequence of humans’ evolutionary biology. It’s a first principle that’s based on evidence and experience, and acknowledges the phenomenology of being human. It asks us to learn from the past by examining tested and successful strategies for being human in a built environment. Design for People also requires that we be forward-thinking, constantly looking to improve how buildings respond to people’s individual and societal needs.

If that all sounds terribly high-minded yet somehow abstract, let me underscore a few very practical ways that we can integrate Design for People in our everyday design process. If you’re reading this article, chances are good that like me, you’re a Vectorworks user, so I’ll specifically address just a few of many Vectorworks tools that you can apply immediately.

Accessibility and Aging

In the jurisdiction where I do much of my work, new residential construction is required to conform to visitability standards to help insure that differently abled people can make use of spaces. As with the more robust ADA standards, often the challenge is simply designing an accessible route given competing agendas of positive drainage and accommodating natural topography. Vectorworks’ Hardscape tool accepts surface modifiers so you can define the elevation and slope of every edge of the surface, and Vectorworks calculates the cross-slope and models the surface itself. In the image below, I’ve highlighted a Hardscape I modified a few days ago for this very purpose. It’s subtle (after all, I want the slopes to be gentle!), but you can see how the tool creates an accurate and suitable surface.

That’s just one example of a tool that helps you make sure your buildings can be enjoyed by everyone.

Breathability

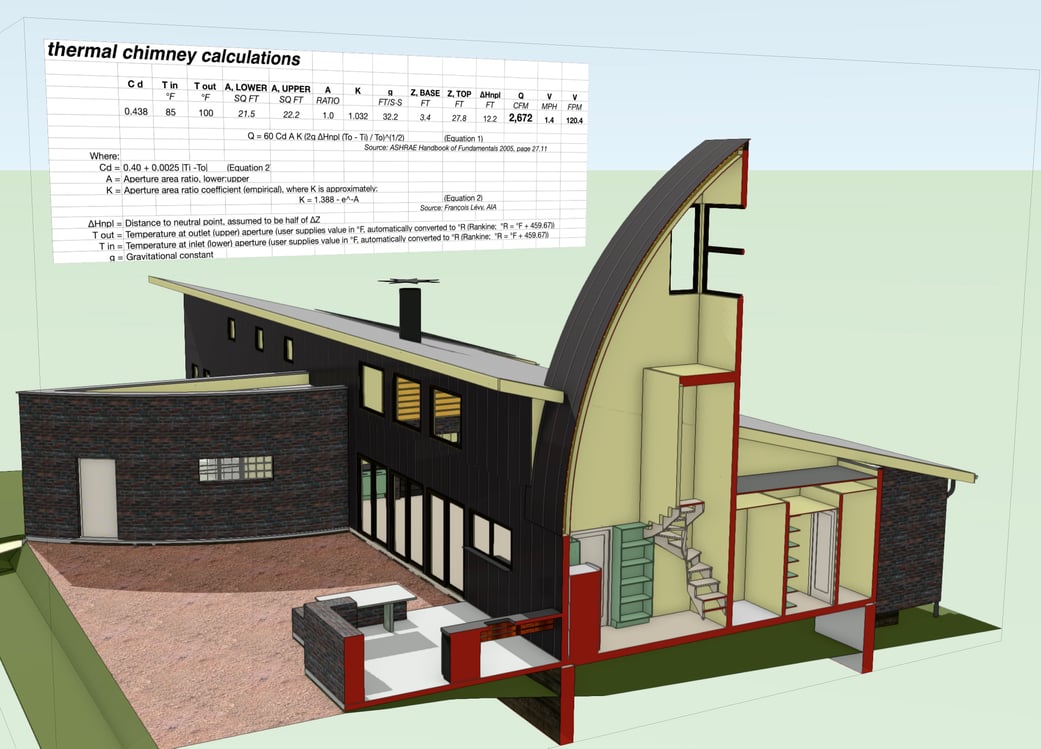

Natural ventilation, in suitable climates and at appropriate times of year, can be a great way to maintain positive indoor air quality and simultaneously reduce energy usage. This is particularly compelling since often the goals of IEQ and energy efficiency can be at odds. Elsewhere I’ve extensively discussed customizing Vectorworks worksheets to estimate airflow rates due to cross ventilation as well as the stack effect of warm air’s natural buoyancy.

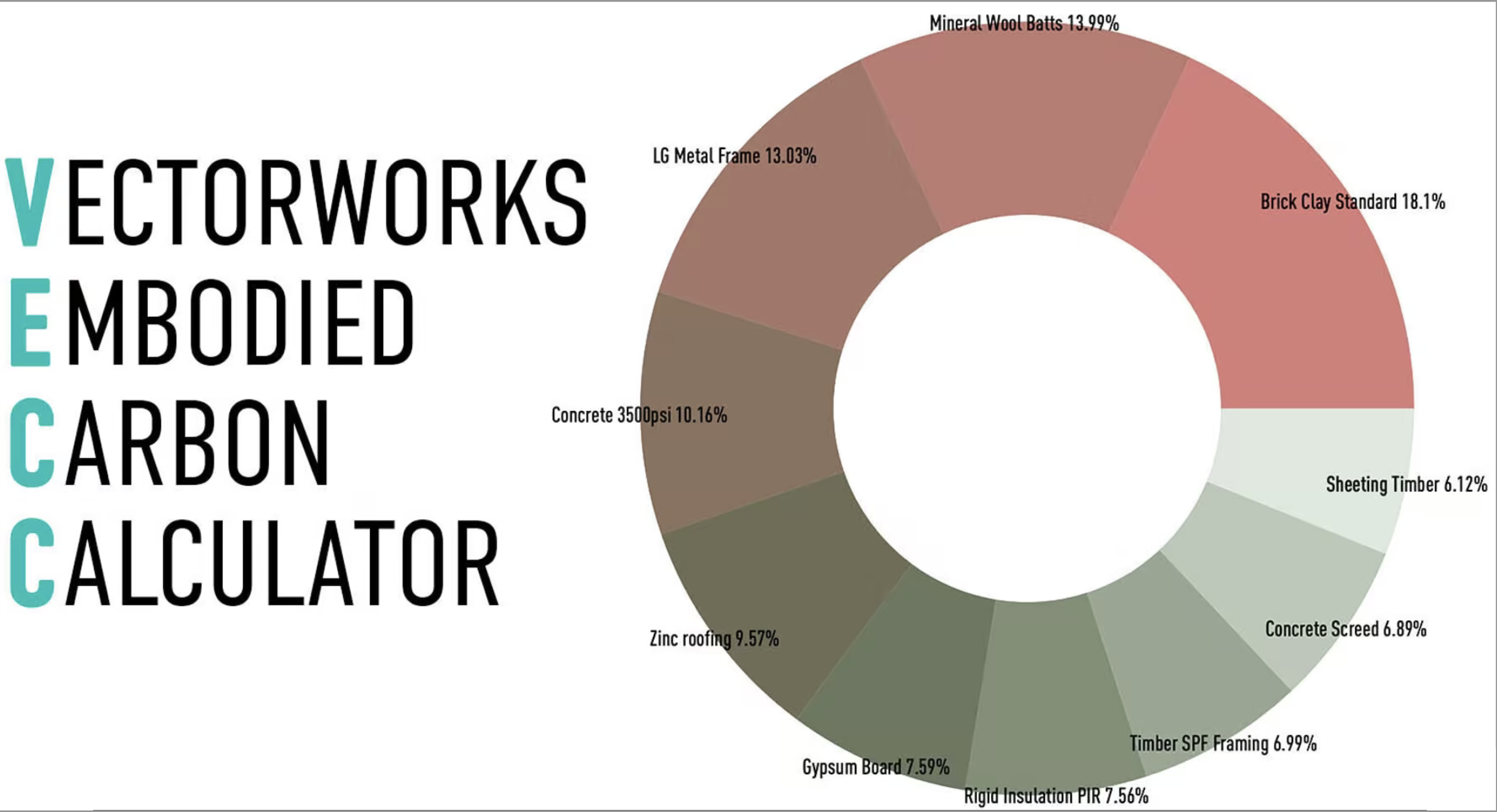

Carbon

Speaking of worksheets, the VECC (Vectorworks Embodied Carbon Calculator) is an impressive embodied carbon evaluation tool based on the Vectorworks’ Materials framework. Using an impressive library of pre-formatted materials that comprehensively carry physical data and graphical characteristics, you can estimate your project’s carbon footprint even in early design phases. Thanks to this powerful tool, you can make informed decisions that materially affect your project’s sustainability when they matter most. And while a seemingly abstract notion like embodied carbon may not directly affect an individual’s experience of your project in the moment, I think we’re all coming to terms with the severity of climate change, and its deleterious effects on all of us.

Daylighting

It’s been well established that humans function better in the presence of natural light. If you’re like me and spend too many nights awake in the wee hours, you’re probably aware of the science advising you to recalibrate yourself to natural diurnal rhythms. In your design projects, you can use simple rendering techniques to validate your daylighting strategies.

Geolocate your project, insert a Heliodon, and run a series of stripped-down renderings that can quickly provide a sense of the effectiveness of your design.

And, of course, the Heliodon’s solar animation feature is an essential tool for evaluating placement of glazing and designing overhangs.

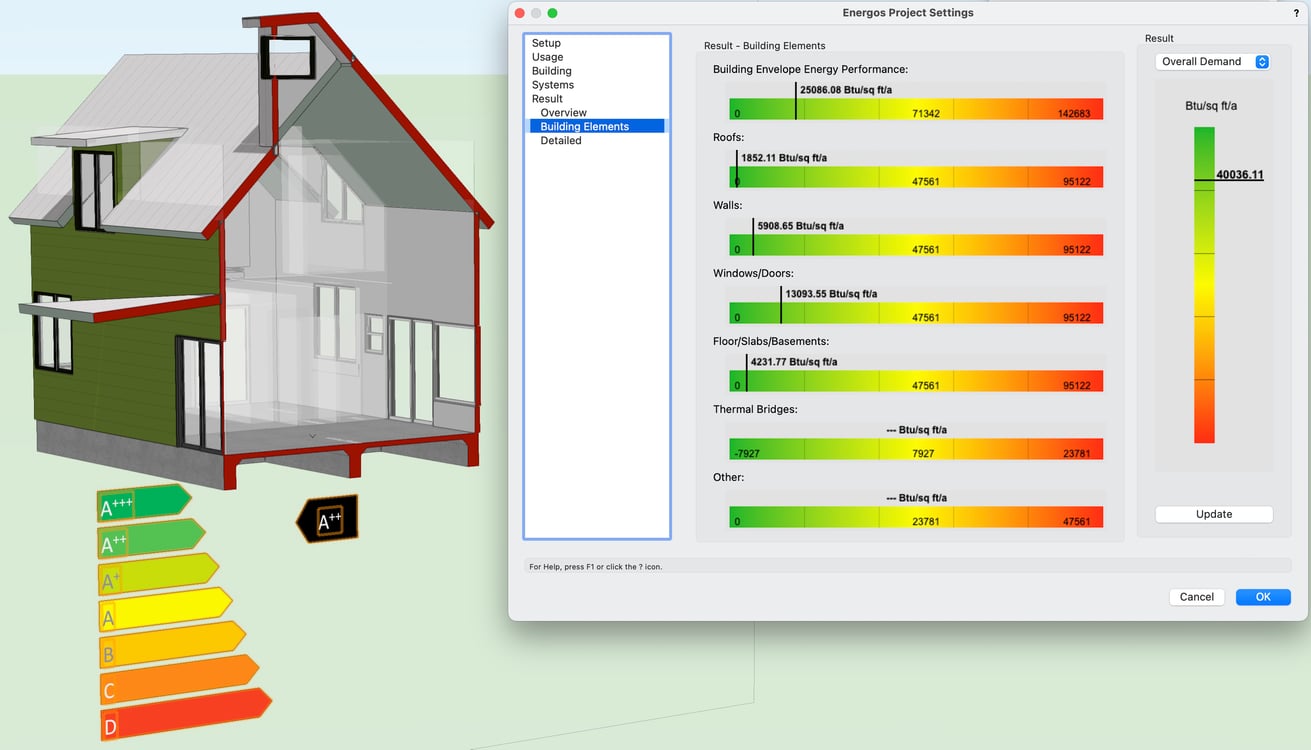

Energy Conservation

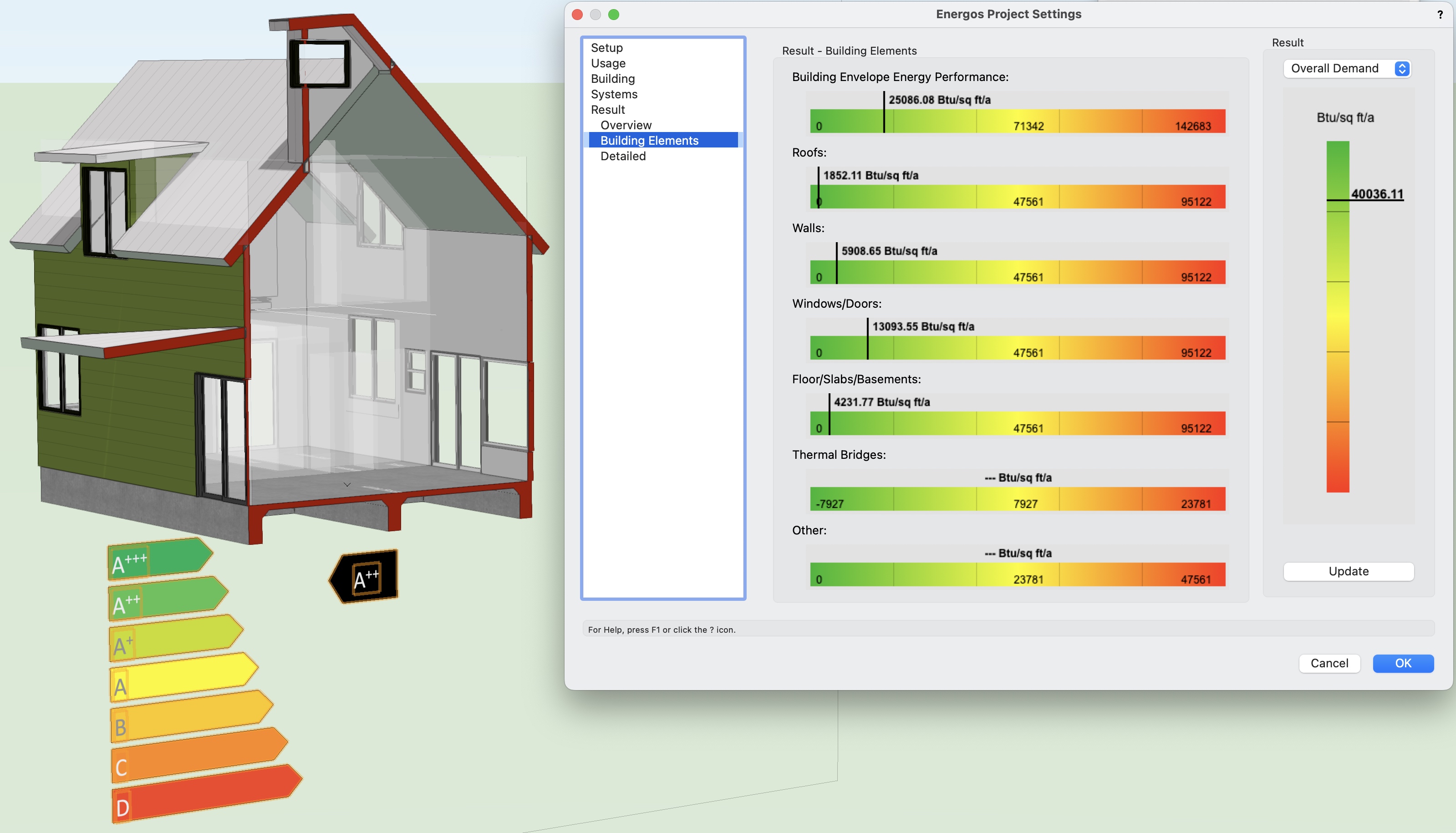

Vectorworks’ Energos suite of tools helps you target energy performance and make decisions to meet those targets. Rather than a comprehensive energy modeling tool (best implemnted late in design), Energos is a Passivhaus-derived calculator that allows you to compare a variety of options to weigh the benefits of a variety of design decisions, from total wall insulation, to airtightness, to window sun exposure, and evaluate where in your project to best devote your efforts.

You may have noticed I’m working my way through the alphabet, and we could keep going. Facilities management with COBie reports; ground strata simulation with site models; I’ve already mentioned the Heliodon; interoperability with allied designers with IFC, and so on.

Principle Two of Architectural Design

The second design principle I’d like to share with you is this:

Design for People

While you may note it bears a striking resemblance to the first one, it’s actually a bit different. In addition to function and purpose, “for” also means in support of and on behalf of.

I don’t have a Vectorworks tool for this design principle, only the promise you made (whether you realized it or not) when you decided to devote yourself to creating buildings. This Design for People principle isn’t something you push forward and strive for; it pulls you. It’s what gives meaning to your work, what brings joy to others.

I’m a slow learner, so it’s taken me quite a long time to see this. When I was in school (and even well into my career), my concern was buildings: designing things. At its best, design school is a safe environment to learn, test your wings, and fail without great consequence (no one gets hurt when you design a dead-end corridor in school). In that sense it’s a controlled simulation of practice, particularly in studio. But while good professors or reviewers may be a proxy, what studio lacks is a client.

It isn’t until practice that you can truly appreciate the joy a client feels when they see a project realized, and it dawns on them that they have been heard, really heard. You’ve translated what they wanted and needed—even if they couldn’t fully articulate it—into a built form that they can inhabit, a space they can fill with their life. This kind of design takes listening aggressively, being open and vulnerable, and being willing to put your ego in its place.

Of course, you shouldn’t set aside your ego entirely, because then you’d just draft up whatever you client dictated, or copy what the next person did, and I think you know that would probably not actually serve your client. But your ego isn’t the rudder, it’s the sail.

.svg)